New Thought-Forms

Spirituality, Science & Spectatorship in Frances Clarke’s The Blue Pearl Project.

– Rob Maconachie, May 2020

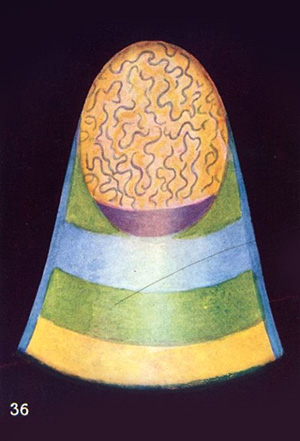

The Appreciation of a Picture

In their 1901 book, Thought-Forms, the British Theosophists Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater reproduce a watercolour illustration captioned with the title, ‘The Appreciation of a Picture.’ (Fig.1) Drawn like a cross-section diagram, the bell-shaped form is divided into green and yellow sections encased within an outer layer of pale blue, from which an egg-like object containing a network of violet-coloured wriggling lines appears to be emerging. The illustration is described as representing thought forms generated by the aesthetic experience of an anonymous viewer as they observed a typical religious painting.

A product of the crisis of faith in Victorian England, Thought-Forms’ Theosophical examination of the aesthetic experience encapsulated a contemporaneous discourse around materialist secularism and the New Age thought of Theosophy, a debate which closely informed the development of early modern art and which has reemerged as a concern for contemporary art practices responding to the current crisis of materialism. Besant and Leadbeter claimed that each definite thought produces a double effect—a radiating vibration and a floating form. Their book reproduced 54 illustrations of these “thought-forms”, each accompanied by a short description along with a chart detailing the meaning of the individual colours used. Writing at a time when centuries of power and politics dictated by the propertied upper classes had resulted in widespread poverty, intolerable working conditions and large-scale civil unrest, Besant and Leadbeater envisaged a spiritually democratized new millenium reaching the zenith of Humanity’s spiritual progress. As Besant makes clear in the introduction, by visualising the impact of the outerworld on the inner, it was hoped that the book would “serve as a striking moral lesson to every reader, making [them] realise the nature and power of [their] thoughts, acting as a stimulus to the noble, a curb on the base.” Read more…

Paralleled by advances in modern art, psychology, feminism and the monumental socio-economic effects of modernization, this desire for spirituality – for feeling and connection through magic, esotericism and the occult–was palpable in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century, a period which saw the most widespread occult revival since the Middle Ages. This same desire is discernible in the current age of advanced capitalism. Dominated by materialism and the dual plagues of gentrification and right-wing politics, the freedom of transcendence offered by spirituality, magic, esotericism and the occult, seems to hold the promise of connection and empowerment, as our awareness of its relation to well-being and mental health continues to grow.

Frances Clarke, Blue Pearl no 17 (from The Blue Pearl Project) , 2020 ongoing, Oil on canvas

Gustave Moreau (1826-1898), The Apparition, watercolour, 72.2 x 106 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The fusion of art, science and occultism within the context of wellbeing was one of the most significant and contradictory features of avant-garde fin-de-siècle culture. Its implications for artistic and curatorial practices have been lasting and numerous, ranging from the nineteenth-century visionary geometries of the naturalist healer, Emma Kunz; the abstract watercolours of the spiritual medium Georgiana Houghton and the holistic diagrams of Hilma af Klint; to Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larianov’s rayonism, Piet Mondian’s theosophical utopianism, Wassilly Kandinsky’s spiritual humanist abstraction, František Kupka’s dynamic colour mysticism and Kasimir Malevich’s Suprematism. These artists’ practices emerged out of a spiritual need, a growing distrust of monotheistic attitudes and a tendency towards comparative religion that began during the Enlightenment and developed throughout the nineteenth-century culminating in the antimaterialist spiritualism of symbolists such as Gustave Moreau (Fig.2) whose evocative and polysemous grandes machines were intended to trigger an experience of spiritual introspection.

Vasily Kandinsky (1866-1944) Improvisation 28 (Second Version) 1912

Oil on canvas, 112.6 x 162.5 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Moreau’s exploration of intuitive nonrational experience and the poetic indeterminacy of the polysemic symbol (which ultimately lead to the development of abstraction) ran parallel to the late-nineteenth-century’s faith in scientific and systematic thought, an attitude which prevails in Kandinsky’s writing a generation later. In Concerning the Spiritual in Art, his 1911 treatise on transcendental aesthetics responding to what he called “The nightmare of materialism,” Kandinsky outlined his theory of an art of spiritual harmony in which he foresaw the “tottering” of positivist science in place of “pure composition.” Indeed, as the American critic Donald Kuspit has stated, “Kandinsky directly challenged the concept at the core of scientific and materialistic philistinism – the power to measure and quantify. Kandinsky’s improvisations resist measure and quantification to the extent that they seem inherently unmeasurable and unquantifiable – altogether beyond scientific control and analysis.” (Fig.3). Somewhat paradoxically, the anti-materialist tendency of Kandinsky’s spiritual abstraction finds a particular resonance in the empirically-based practice of Frances Clarke.

Informed by the Theosophical-based notions of the experience of looking presented in both Kandinsky’s theory of aesthetics and Thought-Forms from which Kandinsky borrowed, Frances Clarke’s research-based practice examines the cyclical framework of the aesthetic experience and its connection to human consciousness. Like Kandinsky, Clarke’s practice considers art as both visually affecting and participatory – a mutually influential circuit operating between artist, object and viewer, which facilitates construction of sites of activity for shared interaction that are integral to the functioning of society. Clarke’s empirical approach however, simultaneously embraces and contradicts the “amorphousness” of Kandinsky’s abstraction, challenging his declaration of the “immeasurability” of the transcendent experience of art, by aiming, like Besant and Leadbeater, at a quantitative analysis of the object/viewer relationship.

Frances Clarke, Blue Pearl no 14 (from The Blue Pearl Project) 2010 ongoing, oil on canvas

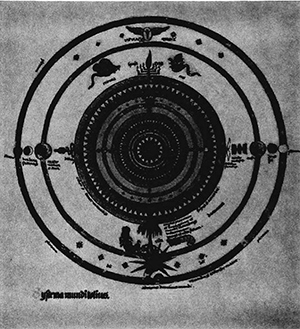

This is the basis of Clarke’s ongoing body of work, The Blue Pearl Project, continues her two-decade-long study of the communicative potential of art and the role of the artist in society. Taking its title from a visual phenomenon associated with meditation, the project is concerned as much with process as with physical outcomes. Supported by Biophysicist Konstantin Korotkov, The Blue Pearl Project comprises a series of non-objective Theosophical-based paintings and the outcomes of an ongoing study which examines the paintings’ impact on viewing participants using Electrophotonic Imaging, or E.P.I, a cutting-edge biotechnology which captures a paintings’ influence on the body’s electrophotonic glow. Informed by Kandinsky’s writings on the spiritual in art and a Jungian reading of sacred geometry in which the circle (the protective circle or mandala, is the traditional antidote for chaotic states of mind) and the triangle are given particular status, Clarke’s diagrammatical paintings are constructed using an intuitive language of glowing mandalas and convergent bands of colour, each charged with an emotional symbolism which is as much personal as universal. (Fig.4 , Fig.8).

Mandala of Modern Man, reproduced in C. G. Jung The Archetypes And The Collective Unconscious,

Second Edition, Translated By R.F. C Hull, Princeton University Press 1969 (First Published 1959).

The project presents Clarke’s paintings side-by-side with the E.P.I. data, creating a paraphysical map of the connective cycle of creativity. By comparing size and colour variations in the images of The Human Energy Field produced by the E.P.I. technology before and after a viewer’s aesthetic experience, Clarke aims to determine how that interaction influences the Human Energy Field. The use of Electrophotonic Imaging technology and the inclusion of the E.P.I. outputs in the project side-by-side with Clarke’s paintings, recognises the particular role photography has played in the iconography of the immaterial realm since the early-twentieth-century. “Like a medium in a trance” to quote the Russian art critic and historian Ekaterina Bobrinskaya, “photographic plates can capture and make visible the invisible. This magical quality of photography, and not simply its documentary nature, played an important role in fin-de siècle culture. It enabled the opening up to the eye of the visible for contemplation and, in addition, created new vectors for painting.”

At the heart of Clarke’s consideration of the object/viewer relationship is a detailed study of the H.E.F. and its role in the development of consciousness. Associated in traditional eastern medicine with the radiant matter produced by the body’s energetic meridians and chakras believed to correspond to organ function and in turn to thought, emotion, intuition and spirituality, Clarke refers to the H.E.F as an interactive invisible electromagnetic field, simultaneously personal and collective, which is inextricably linked to and in constant dialogue with our environment. This way of thinking about the object/viewer relationship positions Clarke’s thinking within a wider discourse around spectatorship and aesthetic experience which developed in art, psychology and anthropology in the century following the publication of the texts already discussed. The study of aesthetic experience during this period was approached from a variety of methodological perspectives, including Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy – a Theosophy for social change, Carl Jung’s explorations of the role of the image in the process of individuation, and Joseph Beuys’ concept of social sculpture. Each expressed a shared concern for processes of transformation, the spirituality of radiant matter and the extension of spiritual power into the mundane sphere.

Radiant matter was the term the Russian artists Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larianov used in relation to their concept of painterly rayonism, a style they developed between 1912 and 1914 in the context of research and practical experiments into the visualisation of invisible radiation. Inspired by writings on the fourth dimension and the realm of cosmic consciousness by the esoteric philosopher, D. Ouspensky, Rayonism aspired to break down boundaries between art and life, taking into account not only that which is externally radiated but also the internal spiritual. Building on the achievements of futurism and cubism, Rayonism replaced modern art’s emphasis on an object’s form, with a focus on the rays of light it reflected and the intersections of these rays in space. In a 1936 letter to the then director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Alfred Barr, Larionov writes: “Rayonism does not investigate questions of space and movement. It means light as the origin of the material and of various types of radiation: radio, infra-red, ultraviolet, etc. […] rayonism means radiation of all types: radioactivity, the radiation of human thought.” Goncharova and Larionov’s approach to visualising the radiation of human thought synthesised existing iconographic structures, the mythology of the etheric body as well as scientific and occult research, in order to begin to construct an understanding of the benefits of the immaterial realm for the material world.

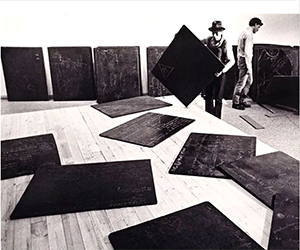

Joseph Beuys installing Directive Forces (Of a new society) 1974-1977, at the Nationalgalerie Im Hamburger, Bahnhof, Berlin 1977, Photo: Fredrich Reinhard, Courtesy Nationalgalerie Im Hamburger Bahnhof

Likewise, Frances Clarke’s imaging of the aesthetic experience is also a synthesis of past and present research, combining the influences of Theosophy in Kandinsky’s writing already mentioned, with the work of more recent artists, including Joseph Beuys. Rayonism’s particular emphasis on “the transfer of the purely philosophical field to the purely physical,” was also the foundational principle of Beuys’ concepts of thinking as form and social sculpture. The concept was literalised in Beuys’s contribution to the exhibition, “Art into Society, Society into Art” held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in 1974, in which, over the course of four weeks, Beuys completed 100 blackboard diagrams during discussions around the principles and goals of his thinking. (Fig.5) Arranged on the floor like relics of a still ongoing process, Beuys proposed the work as a “permanent school” where the artist, the artworks produced and the spectators who took part, participated in a free expansion of creative concepts. The stress here on “expansion” and “processes” implies warmth generated by the friction of thought. A similar “warming” is at work in Beuys’ Fond sculptures, in which piles of layered felt, iron, and copper, are used to produce the same metaphor. The functioning concept of the Fond sculptures was the accumulation of warmth to supply the power for the transformation of matter, and by extension, of spirit. Beuys called these pieces “static actions” because they rest in one place and yet imply activity. Like Kandinsky, Beuys was a follower of Rudolph Steiner whose system of Anthroposophy proposed that a new consciousness could be achieved through thinking with the heart. Steiner called this Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition and it provided Beuys with the working concept for his own overarching theory of social sculpture – that art and life are balanced between chaos and form in which the equilibrium is maintained by the heart. Through heart thinking, Beuys suggested, truth is experienced via intuition, as it is in the intuitive moment that truth presents as a reality.

In The Blue Pearl Project, Clarke animates inanimate matter in a similar way to that in which Beuys transforms spirit. Tracing the flow of energy from artist to object to viewer using electrophotonic imaging technology, Clarke emphasises the interconnectivity of the aesthetic experience in which the artist’s bio-energy– enmeshed within the painting in the process of creation,–is transferred to the viewer in their moment of appreciation and passed on in turn via that viewer’s future interactions. As Clarke has explained in relation to this process: “Abstract ideas develop and transform through resonance with inner planes in nature – which are in truth external and all around us in energy fields – the natural process of art means that it essentially charts a history of feelings, thoughts, ideas and encoded bio-information within the morphic fields that are passed down through time, creating, in effect, an inheritance framed forever on the canvas. The painting becomes a Holon – something that is simultaneously a whole and a part.” In this way Clarke’s practice synthesizes Steiner’s anthroposophy and the theosophy of Besant and Leadbeater in its insistence that spiritual investigation must lead to social change.

In visual art, the relationship between the art object and the spectator has been rigorously worked over in the wake of Besant and Leadbeater’s Thought-Forms. Curatorially, beginning in the 1970s and continuing throughout the 1980s, it was examined through exhibitions which underscored artists interest in spirituality, not least of which, as Pietro Rigolo has noted, Harold Szeeman’s Junggesellenmaschinen, Monte Verità and Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk, which presented “artistic practice as a means for spiritual elevation and as a guiding star indicating the path towards and equal and sustainable development.”Other exhibitions followed, including The Spiritual in Art at the Los Angeles County Museum in 1986 curated by Maurice Tuchman, which set out to prove the genesis and development of abstract art were inextricably tied to spiritual ideas current in Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Other shows in New York that same year, at P.S.1 and the New Museum of Contemporary Art, as well as that year’s Venice Biennale, Art and Alchemy, also revealed mystical and occult pockets within contemporary art and the degree to which 20th-century artists had been attracted to esoteric concerns. More recently Intention to Know curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev in collaboration with Theaster Gates at the Stony Island Arts Bank, in Chicago in 2016, featured the work of three artists, Erin Hayden, Lea Porsager and Cauleen Smith which responded to Annie Besant’s illustrated writings.

These exhibitions positioned the art object in an alternative context to that attributed to it by Western modern materialism, in which art has traditionally been understood as a form of high culture detached from everyday life and participated in through the established norms of connoisseurship, patronage, and individual expression; a system which places meaning within the object as commodity. In this advanced capitalist art world, as the American critic Donald Kuspit has stated (summarising Greenberg), “the idea of the spiritual as such, has become meaningless, thus completing the process of the despiritualisation or demystification of art that began with Cubism and climaxed in post-painterly abstraction.”

This same despiritualisation tendency in American art of the 1950s and 1960s is observed in Lucy Lippard’s The Dematerialisation of Art, which posits that the rational empirical-based art of the post-painterly abstractionists would remove the aesthetic object as the central focus of art and art would be freed from commodification. Lippard’s conceptual basis lay in the five historical categories of aesthetic phenomena outlined by Joseph Schillinger in The Mathematical Basis of the Arts: 1) the “pre-aesthetic” phase of mimicry; 2) ritualistic or religious art 3) emotional art 4) rational, empirical-based art and 5) “scientific” or “post-aesthetic” art, this final phase culminating in the liberation of the idea and the disintegration of art.

Kandisnky identified an earlier iteration of this process in Concerning the Spiritual in Art, in which he identified Impressionism as the nightmare of materialism facing turn-of-the-century Europe. In our current moment of advanced capitalism, as Donald Kuspit has put it: “we have not only not awakened from the nightmare of the materialistic attitude in art and society, but materialism has become a plague, indeed, the reigning ideology in both.” The penultimate expression of this devolution in art is, according to Kuspit, the soulless empirical abstraction of Frank Stella and Elsworth Kelly and the synthetic Pop Art of Andy Warhol, which have stripped art of its spiritual import and continue to proliferate the objectivity and externality of twenty-first-century visual culture. Kuspit calls for a return to the spiritual in art as the only type of art that makes sense in threatening modern times. This responsibility lies with the maker.

In considering art and culture from the point of view of the maker, the American anthropologist Ellen Dissanayake has used the term ‘making special’ in regard to the wider participatory role performed by producers of cultural artefacts. Dissanayake suggests that regarding art as a behavioural instance of, ‘making special’, “shifts the emphasis from the modernist view of art as object, or quality, or the postmodernist view of it as text or commodity, to the activity itself (the making or doing and appreciating)…” This idea of the “use-value” of cultural artefacts which Dissanayake’s terminology implies, and the emphasis she gives to the spectator’s moment of appreciation of the object, find analogous concerns in Clarke’s The Blue Pearl Project, in which Clarke’s paintings are not mere commodified objects, but functional elements within a cyclical relationship connecting the artist, the object and the viewer – a tripartite cell which reproduces infinitely forming a globally interconnected structure of similar but essentially unique aesthetic experiences. Using the example of pre-modern societies, Dissanayake considers the object itself as secondary to its use, citing instances in which the object is, “essentially an occasion for, or an accoutrement, to ceremonial participation.” In the present day, this might be compared to the collective endeavour of sewing a handmade quilt, in which the activity of making (the interconnectivity essential to its process) may be as, if not more, important as the final product.

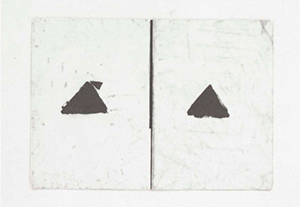

Vassily Kandinsky, (1866-1944) Color triangle, ca. 1925 – 1933, 32 x 32 cm, Graphite and gouache on paper

Getty Research Institute Los Angeles

Approaching the object/viewer relationship from the same perspective of collective participation, Clarke’s diagrammatic paintings from the The Blue Pearl Project series are concerned not so much with what art can be rather than with what it can do. The artists and thinkers discussed above – Besant and Leadbeater, Kandkinsky, Beuys and Steiner – all present this ‘doing’ or ‘verbing’ of art – this making an action of thought – through the use of diagrams. In Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandisnky wrote that “the life of the spirit could be represented in a diagram as a large acute-angled triangle divided horizontally into unequal parts with the narrowest segment uppermost.”(Fig.6). And Just as Steiner taught his philosophy — a “scientific” discipline — by drawing diagrams with chalk on sheets of black paper pinned to the wall, so too did Beuys. And like Kandinsky, via Steiner, Beuys’ practice also foregrounds the importance of triangles, in both his sculptures and actions; particularly in the context of his Manresa and associated drawings. (Fig.7). In Clarke’s Blue Pearl Project paintings, the triangle appears as it does in Kandinsky writing as representative of the life of the spirit and moving steadily upward, following the path of the visionary artist (Fig 2). In this way Clarke’s paintings also perform like diagrams in which the subtle worlds of matter, feelings and thought are given form and existence as material entities.

The relationship between artist and viewer which Frances Clarle’s work establishes is linked closely to Theosophy, Anthroposophy and the work of Joseph Beuys. Emphasising the communicative power of the inner spiritual world, these practices revolutionised the critical discourse around the object/viewer relationship, which since around 1970 has held heightened importance in contemporary art theory and practice. As a result of this return to the spiritual, art has come to be understood as a significant element in the constitution of social relations. As Thomas Frangenberg and Robert Williams have written from a post-formalist context in regard to the experience of the beholder, “we now recognise that meaning is produced by an interaction between the work, its environment, and the viewer.” In other words, the meaning of a work of art is no longer considered to be something contained exclusively within it. This is what Besant and Leadbeater were aiming at in their Theosophical diagram of the appreciation of a picture. But whereas, as Theosophists, Besant and Leadbeater foregrounded the individual, it is the wider collective and social implications of spirituality with which Beuys, Steiner and Kandinsky were concerned and which is validated by association in Frances Clarke’s work.

Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), For Felt Corners , 1963, Oil and dirt transfer on facing inside covers of a sketchbook, mounted on cardboard, 50.6 x 36.7 cm. , Ludwig Rinn Collection

Clarke sees the body as an open system, constantly exchanging matter, energy and information with the environment. Her approach shares with the artists discussed a concern for the study of energetic phenomena and an attempt at a visualization of the effects of aesthetic experience, an essentially Humanist endeavour synthesising occult religion, philosophy and science, according to the principles of Theosophy. Co-founded by Helen P. Blavatsky in 1875 The Theosophical Society had, and continues to uphold, three main aims: to form a nucleus of the universal brotherhood of humanity without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste, or colour; to encourage the study of comparative religion, philosophy, and science; and to investigate the unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in man. In the closing sentence of her 1889 book, The Key of Theosophy, Madame Blavatsky writes, “earth will be a heaven in the twenty-first century in comparison with what it is now.” Here, amid the fallout from Blavatsky’s hoped-for future, that dreamt of utopia has become a living nightmare far beyond even that “evil, useless game” identified by Kandisnky. The would-be Theosophic paradise has been reduced to rubble by the bloodiest and most destructive century in human history, and a virus for which there is no known cure haunts its ruins. The fortunate, and I confess to being one of them, have had it easy for far too long. In 2020 one becomes aware of what Buddha was aware of when he left his pleasure garden and went out into the world and saw the sick and the dead and couldn’t believe these things existed. He wanted to know, not just believe.

What one is left with from this consideration of the experience of beholding, is a sense of the urgent need for a new age of spiritualism. We must reaffirm the spiritual in art if our societies are to survive. We must slow down, retreat from the consumer surface-level culture of Pop and look inwardly. Rather than a dis-integration of the object, this new spiritualism would see a return to the integration of the contemplative object into society; a society in which art is integrated within a path towards equality and a new sense of community. Frances Clarke’s Blue Pearl Project invites us to take a step closer to this mode of thought. Her socially, spiritually and scientifically engaged practice stems from a belief in the innate interconnectivity of all things; human, non-human, animate and inanimate. By visualising art’s relationship to the wellbeing of the inner spiritual world, Clarke speaks to our social obligations in the outer world; to our social contract with one another. Her insistence on the ethics of aesthetics creates a useful and powerful art with which to build a more equitable, sustainable and spiritually robust society.

Endnotes:

- 1. Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater, Thought-Forms, Project Gutenberg EBook, Release Date: July 12, 2005 [EBook #16269] originally published by The Theosophical Publishing House Ltd, London, 1901.

- 2. Kandinsky’s occult library was considerable, but Thought-Forms in particular fuelled his speculation, as did Leadbeater’s Man, Visible and Invisible 1902, and Rudolf Steiner’s, Theosophy, 1904

- 3. Ekaterina Bobrinskaya, “Mikhail Larionov: Rayonism and Radiant Matter”, Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, Volume 284, 2018

- 4. Variously referred to (with some slight variation in denition) as animate matter, grey matter, energetic matter, etheric matter, the etheric body, astral matter, subtle matter, aura. Kandinsky discusses this in a footnote in Concerning the Spiritual in Art where he writes: ”Frequent use is made here of the terms “material” and “non-material,” and of the intermediate phrases “more” or “less material.” Is everything material? or is EVERYTHING spiritual? Can the distinctions we make between matter and spirit be nothing but relative modications of one or the other? Thought which, although a product of the spirit, can be dened with positive science, is matter, but of ne and not coarse substance. Is whatever cannot be touched with the hand, spiritual? The discussion lies beyond the scope of this little book; all that matters here is that the boundaries drawn should not be too denite.” Wassily Kandinsky Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Project Gutenberg EBook, Release Date: March, 2004 [EBook #5321] Translated By Michael T. H. Sadler. Originally published in 1910.

- 5. In exploring this idea, Goncharova produced abstract works such as Rayonist Composition c.1912 –13.

- 6. Mikhail Larionov. “Rayonism” (1936) in N. Goncharova, M. Larionov. Research and Publications, Moscow, Nauka, 2003, p. 97–98, quoted in Ekaterina Bobrinskaya, Mikhail Larionov: Rayonism and Radiant Matter, Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 284, 2018.

- 7. Ilia Zdanevich. “Nataliya Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov” in Ilia Zdanevich, Futurism and Vsechestvo 1912–1914, vol. 1 Moscow: Gileya, 2014, p. 115

- 8. Ann Temkin and Bernice Rose, with a contribution by Dieter Koepplin, Thinking is form: the drawings of Joseph Beuys, Philadelphia Museum of Art; The Museum of Modern Art, 1993

- 9. Ann Temkin and Bernice Rose, Thinking is form : the drawings of Joseph Beuys, with a contribution by Dieter Koepplin, Philadelphia Museum of Art; The Museum of Modern Art, 1993

- 10. Frances Clarke, The Blue Pearl Project, 2019

- 11. Rigolo Pietro, “Instilling in humanity warmth and a new spiritual light – Theosophy and Modern Art in Harald Szeemann ’s exhibitions” Academia.com, accessed 28/05/2020

- 12. Donald Kuspit, “Reconsidering the Spiritual in Art” presented as a Lecture at the School of the Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, 2003.

- 13. Ellen Dissanayake “The pleasure and meaning of making” American Craft 55(2), 1995: 40-45

- 14. Thomas Frangenberg and Robert Williams, The Beholder: The Experience of Art in Early Modern Europe, Ashgate, 2006

- 15. Donald Kuspit used this analogy in his above mentioned lecture.